A Brief History of Puducherry: Interview with Historian Jean-Baptiste Prashant More

The Inception Meeting of S20 will be held on the 30 and 31 January 2023, in Puducherry (it is better known as Pondicherry, its former name). It has a long and rich history, dating back to at least the 3rd Century BCE. In this interview, Jean-Baptiste Prashant More, a French historian of Indian origin, traces the history of Puducherry and highlights its connection with a few significant historical figures.

More obtained his PhD at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences) in Paris. Accomplished in French, English and Tamizh, he has authored several scholarly papers and books on South Asian history. He has a particular interest in Puducherry, where he was born and raised.

There’s an archaeological site in Puducherry, only about 4 km south of the capital city, called Arikamedu. What is its historical significance?

The name “Arikamedu” does not appear in any Indian literature, be it Sangam or medieval literature. It appears first only in the colonial period during the French land survey in the 19th century as “Aripu medu” or a “mound eroded by the sea”. The mound is found to the east of the Ariankuppam River which joins the sea here. But we know that Arikamedu was a settlement that existed about 2,000 years ago and that it was an important trading centre based on the excavations that have been carried out here.

In the late 1930s, Jouveau Dubreuil, a French Indologist, found some artefacts from this place. He invited well-known Indian and foreign archaeologists like Mortimer Wheeler to study Arikamedu. The first dig found many more artefacts and it was confirmed that they were from about 2,000 years ago. This would be during the time of the Early Cholas. Most of the artefacts were either made here to be exported to Rome or were made in Rome and imported here. This was again confirmed by excavations carried out in the 1970s by a team led by archaeologist Vimala Begley.

The excavations show that the Arikamedu settlement had many brick walls and wells. It had a well-laid central drainage system with secondary drainages. The artefacts that were found here include lamps, glass beads, stone beads, wooden beads, wood blocks, pots, rings, Amphorae [clay jugs], Arratine ware [clay table ware with a glossy surface], figurines of Pillaiyar [Ganesha], seals and so on. Based on this, archaeologists have concluded that Arikamedu traded with foreigners, especially Romans.

The Arikamedu settlement seems to have existed until the 3rd century CE. What happened after that and how did the town of Puducherry come to be?

The villages around Puducherry existed for many centuries. The region changed hands many times during the medieval period. It was ruled by the Pallavas, the Pandyas, the [Later] Cholas, the Vijayanagara Kingdom, the Marathas and the Bijapur Sultanate. The Cholas built a string of Shivan temples in this region, including the famous Villianur temple. We do not know whether Puducherry town existed then – it probably did not since nothing is mentioned in the records. But we know that it existed before the Europeans arrived. The first reference to it is found in the writings of the Arab navigator Sulaiman-al-Mahri at the turn of the 15th century – he referred to “Pondicherry” as “Bandikeri”. Later on, the Portuguese refer to it as “Puducherry” which means “new town”.

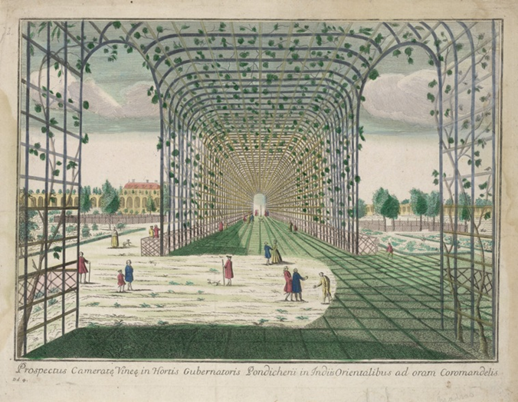

The French came to Puducherry in 1673-1674. They got a settlement there from Sher Khan Lodi, a vassal of the Bijapur Sultan in that area. They later expanded the settlement by getting land from other Sultans. François Martin was the founder of modern Puducherry [he was its first Governor-General].

How and when did the Europeans arrive in Puducherry?

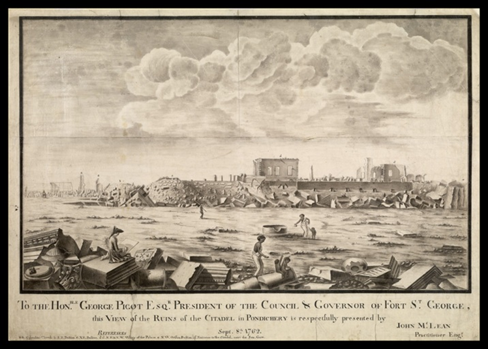

They arrived when the region was ruled by the Nayaks of Gingee who were dependent on the Vijayanagara Empire. It was developed as a port by the Gingee Nayak Muthu Krishnappa [1601-1609] who wanted to improve trade in the region, and so he invited the Portuguese to settle in Puducherry. It was then successfully occupied by the Portuguese, the Dutch, the Danes, and finally, the French, who settled here and prospered. They then had several fights with the British, who by then ruled over most of India and also wanted to conquer Puducherry. The British succeeded twice but on both occasions returned it back to the French – once in 1763 and again 1814. The British also left Karaikal, Mahe, Yanam and Chandannagar for the French [the first three are still officially part of the Union Territory of Puducherry]. After the second treaty, they returned Puducherry on the condition that the French would abstain from raising an army again. This is how it became a thoroughly French territory.

What was French rule like?

From 1820s onwards, the French Government took real interest in developing Puducherry, according to its own vision of development. They established schools, regulated land ownership, and carried out other major reforms. French became the medium of instruction but Tamizh was also taught in schools (and also Malayalam, Telugu, and Bengali in Mahe, Yanam, and Chandannagar respectively).

After the French Revolution, the French adopted a parliamentary system and this had an influence on Puducherry as well. To the great surprise of even the British, the French introduced electoral democracy here in 1871 itself. There was also a representative from Puducherry to the French Parliament. This was welcomed by many people who had sought refuge in Puducherry, like Subramania Bharati [Bharati was a writer, poet, social reformer and a nationalist]. Many French people moved here and, unlike in British India, they moved freely with the local people. Bharati, in fact, wrote several times in his Tamizh newspaper that France was the mother of democracy.

You have studied the life and work of Subramania Bharati closely. What was his early life like? How did he end up in Puducherry and how did life there influence his work?

Bharati was born as C Subramanian in 1882 in a place called Ettayapuram in Tirunelveli District [Tamil Nadu]. He had his early education in Tirunalveli. He later went to Benares [Varnasi] for his high school. The Ettayapuram Zamindar met him when he had gone up north. He asked Bharati to come back and work in his palace as a kind of librarian. Bharati agreed. By this time, his greatness with the Tamizh language was becoming well-known. When he came to work for the Zamindar, he was given the title of “Bharati” in the Ettayapuram court. That’s how he became Subramania Bharati. But he did not stay for long here.

He then joined the Sethupathy school in Madurai as a Tamizh teacher. During this time, the editor of a Tamizh newspaper, Swadesamitran, in Madras [now Chennai] asked Bharati to join him as a sub-editor. This was in 1905 when he was still in his early 20s. In the meanwhile, a friend of his called Mandyam Srinivasachary started a new Tamizh newspaper called India. Bharati became its editor. He was also editing a women’s magazine called Chakravarthi. Later, he also started an English magazine called Bala Bharatam. Even though he had only done his matriculation and not studied English formally, he wrote in impeccable English.

From this vantage point, Bharati was closely following the political developments in the country. The Congress party, which was formed in 1885, was divided into the moderates and extremists. The extremist faction was led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal. Bharati, along with VO Chidambaram Pillai [also a freedom fighter who started a shipping company], was greatly influenced by the thinking of the extremists. In 1908, a few people died in an agitation against the British led by Chidambaram in Tirunelveli. Chidambaram was arrested. The British were arresting other nationalist leaders as well. Bharati too was about to be arrested. So, in September 1908, he escaped to Puducherry.

When he came to Puducherry, he started to republish newspapers like India, Vijaya, and also newspapers that were published by Aurobindo [Ghose] in Bengal like Karmayogin and Dharma.

While in Puducherry, he also wrote monumental literary works like Kannan Pattu, Panchali Sapatham, Kuyil Pattu and so on. More than 70% of what he wrote was written when he was in Puducherry. He also started indulging in social reforms. He made no distinction between human beings and fought against caste system.

During this period, he made friends with many French people and learned the language. He was infatuated with the values of France. Even on his papers he would put this slogan of liberty, equality and fraternity – Swatantaram, Samatvam, and Saghotarattuvam – in Tamizh. He believed that these values could save the world. He also read the writings of French revolutionary thinkers like Voltaire and Rousseau.

But in a few years, the British had ensured that his publications did not enter the Madras Presidency. He sunk into poverty – he did not know anything other than writing. He also had to look after his wife and two children. He could not afford house rent. Sometimes, when his landlord asked him for the rent, Bharati would sing one or two of his songs and the landlord would go away. But poverty and ill-health forced him to leave Puducherry and he went to Madras [here, he was arrested by the British but released because of his condition]. He died in 1921 – his death was terrible [his health worsened after he was attacked by a temple elephant in Chennai].

So without him coming to Puducherry, it would have been impossible for Bharati to emerge as a Mahakavi, even though he was in poverty. But he was not immediately recognised as one. His big literary works were not published until after his death. That is why there is a memorial of Bharati in Puducherry, built where he stayed with his family.

Tell us about the association of Aurobindo Ghose with Puducherry – the Sri Aurobindo Ashram is an important part of its identity.

Aurobindo also belonged to the extremist faction of the Congress. He had been accused by the British of involvement in terrorist activities in Calcutta [now Kolkata]. So, he also escaped to Puducherry. When he arrived in Puducherry, he was welcomed by Bharati and other nationalist leaders at the beach. Bharati assumed that Aurobindo would take a lead in the nationalist movement in Puducherry. But Aurobindo changed course suddenly and he mellowed down – he became a spiritualist. At that time, a Frenchman called Paul Richard and his wife [Mirra Alfassa] had come to town as well. His wife was none other than the person who would eventually be called “The Mother”. Richard was a philosopher who wanted to get elected to the French National Assembly and he sought Bharati’s help. Bharati canvassed for him and during this time, he introduced Richard and his wife to Aurobindo.

Aurobindo and Richard started Arya, a journal of philosophy. Aurobindo used to write regularly in this journal, and he also wrote books like The Life Divine. But somehow Bharati could not see eye to eye with this philosophy. Once he went to meet Aurobindo and saw that there were people who were prostrating in front of him because they believed Aurobindo had become an enlightened person. Bharati believed that all humans are equal, and no one is superior or inferior to another. So he parted company with Aurobindo. Aurobindo then developed what he referred to as the supermind philosophy and eventually established the Sri Aurobindo Ashram with Mirra.

Puducherry also has a Subhas Chandra Bose connection. Is that correct?

Yes. The French had established a colony in Indochina – it comprised Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos – in the 1870s. Many people from Puducherry migrated to Indochina to carry out business and for employment. One of the families that went to Saigon [now Ho Chi Minh City] was the landed family of Prouchandy. A member of the family, Leon Prouchandy, became a social reformer in Indochina.

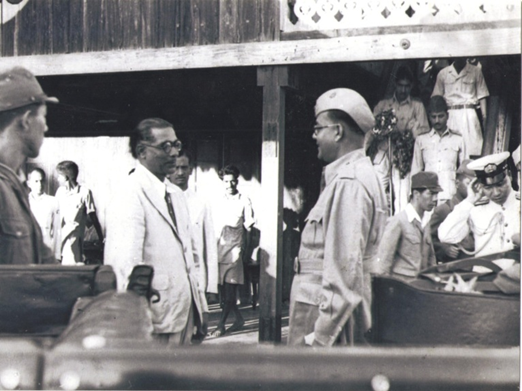

It was then that Subhas Chandra Bose had revived the Indian National Army (INA) and the Indian Independence League (IIL) in Southeast Asia and was raising money to help liberate India. Many Indians, especially Tamizh people there, helped Bose with cash and jewellery. One of those who contributed generously to Bose’s campaign was Leon Prouchandy. He was the only person from Puducherry who took a stand in favour of Bose [and, therefore, against France who were part of the Allies]. 99% of people from Puducherry were pro-French at that time. His mansion in Saigon served as the Secretariat of the IIL. Thus, he became very close to Bose. When the Japanese were defeated by the Allies in World War II, Bose fled Southeast Asia, only to disappear a few days later. Prouchandy was arrested and tortured by the allied forces.

How did Puducherry join India?

How this came about is quite intriguing because until 1947, when India got its Independence, there was no real freedom movement in Puducherry. It gathered momentum in 1954 after a man called [Edouard] Goubert, who was of Franco-Indian descent, and associates like Muthukumarappa Reddiar and HM Kassim, said that they wanted to join the Indian Union. It was he who was instrumental in ensuring that Puducherry joined India, but under the condition that it retained its cultural identity. Goubert joined hands with Jawaharlal Nehru, with whom he was very friendly. But there was no referendum of the people as was required by the French constitution. Instead, the people’s representatives – who were mostly supporters of Goubert – voted to make Puducherry an integral part of the Indian Union.

The Indian and French governments signed a treaty in 1956 that allowed Puducherry to join India, but with certain conditions. It was ratified by the French and Indian Parliaments in 1962.

Would it be fair to say that Puducherry not only nurtured many historical figures but also gained from them?

Yes. Take the case of Bharati. His stay in Puducherry, where he lived for 10 years, was a great boon for the people here. Without him, Puducherry wouldn’t have acquired a nationalist streak. Puducherry was enriched and became famous because of people like Aurobindo, Bharati, Prouchandy, and Goubert. And in turn, they, particularly Aurobindo and Bharati, became famous because of Puducherry. Today, we have the Aurobindo Ashram and the Bharati Memorial to celebrate them, and we also have memorials for Bose, Prouchandy and Goubert. It has thus become historically important even though it is a small place.

– Karthik Ram